Upstate N.Y. Has A Message For Trump 2020: Reelection Won’t Be Easy By Luke Perry

I have recently done a great deal of research, speaking with voters and poring over polling, to determine why House Republicans in nationally competitive districts lost their seats last November. A few important findings from this deep dive into data provide a valuable starting point for understanding Donald Trump’s reelection prospects in 2020.

One: A strong economy is not helping the president’s overall approval rating.

More Americans contend the economy is doing well than any other point since 2001. Trump’s economic approval peaked earlier this month at 55%, but his overall approval is still in the 40s.

Unemployment has fallen one point since Trump took office, while the GDP growth rate rose one point. This is good, but not a resounding case of “better off than four years ago,” like Barack Obama presiding over the end of the Great Recession, particularly as Trump’s unorthodox style, welcomed by some, has disoriented many.

Americans also care a lot less about the economy post-Recession, pushing it down the list of 2018 voter priorities. Democrats, who are united in opposition to the president, are more concerned than Republicans, and unlikely to reward Trump or support his economic policy prescriptions.

The economy did not enable Republicans to retain the House and cannot be counted on by Trump to retain the presidency.

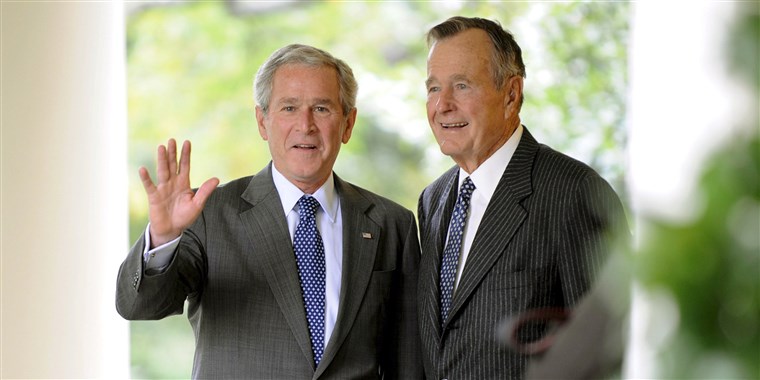

Photo by Matthew Cavanaugh/EPA

Two: Incumbency is beneficial, but not determinative.

Over the last 40 years, just one presidential incumbent failed to be reelected, George H.W. Bush in 1992. Bill Clinton was aided by conservative-leaning third party candidate Ross Perot, who won 19% of the popular vote.

Eight of 11 presidents have been re-elected since the establishment of term limits in 1951. Since 1932, there has only been one instance of a party controlling the presidency for less than eight years, Jimmy Carter (1976-80).

There is one major difference between Trump and these presidents: All but one (George W. Bush in 2000) has not sought reelection after losing the popular vote. And Bush’s popularity grew immensely after 9/11, with widespread support for the war on terrorism.

Trump has experienced no such bump. His approval ratings have been incredibly steady, largely due to his polarizing persona. If Trump doesn’t expand his base, like Bush did, he will likely lose.

Photo by Jason Reed/Reuters

Three: Trump has simultaneously energized and divided the Republican Party.

Trump underperformed with Republicans in 2016. The last three Republican presidential nominees all received 93% GOP support. Trump was five points shy of this mark.

This may not seem like much, but it can make a difference. Five percent of Republicans constitutes 1.6 million people, more than the respective populations of 10 states.

Damage was minimized in 2016 since Trump was one of two abnormally unappealing candidates. If Democrats avoid nominating someone historically unpopular, they will have a distinct advantage.

In 2018, GOP House incumbents struggled to navigate the Trump presidency; 21 lost their seats, including those who closely aligned with the president. Claudia Tenney (N.Y.-22) failed to be reelected in a district the president won by 15 points, while embodying the president and hosting the entire Trump family on the stump.

Tenney received a paltry 65% support among Republicans, roughly one-third of whom did not care for the president’s Tweets, lack of leadership and learning on the job. This could spell trouble for Trump in 2020 swing states.

Photo by AP

Four: All politics is local.

All elections are local, even presidential elections, where candidates must cobble together enough states to win a majority in the Electoral College.

Trump’s 306 Electoral College votes seems large compared to Hillary Clinton’s 232, but was among the 12 closest presidential elections in U.S. history, thanks to the 36 votes by which Trump exceeded the 270 requirement.

Margins in several key states were incredibly thin. Trump won Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania — three consistently Democratic states — by less than 1 percentage point each. All three elected a Democratic U.S. senator and governor in 2018 as Trump’s public opinion fell.

Prior to the midterm, Trump had 43% approval in Michigan and Wisconsin, and 46% in Pennsylvania, while majorities in each state disapproved of the president.

Newly elected Democratic Reps. Anthony Brindisi (N.Y.-22) and Antonio Delgado (N.Y.-19) model how a Democratic nominee can compete contested political terrain and perhaps regain pivotal Midwestern states. Both prevailed as competent and accessible moderates who prioritized town halls, bipartisanship and local issues.

The 2020 elections will test if Donald Trump’s tenure was an aberration or indication of lasting change to party politics. Trying to replay the 2016 campaign is unlikely to be successful.

This article was originally published in The New York Daily News on May 21, 2019.

Luke Perry is a professor of government and politics at Utica College and author of "Donald Trump and the 2018 Midterm Battle for Central New York.”