Dispatch from Eastern Europe: Restless Balkans By James Bruno

The Balkans, ethnically and geographically, were tailor-made for turmoil, another period of which we may be entering.

Photo from James Bruno

The man on the far right of the above photo is former Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu attempting to calm tens of thousands of angry citizens as he tried to deliver what would be his last speech on December 21, 1989. The center photo shows the balcony of what was the Romanian Communist Party headquarters (one of the flags is of the EU) where he stood that fateful day with his wife Elena, who was as despised as he was. The man on the far left is Egmont Puşcaşu, a minor celebrity hero of the Romanian Revolution, who, at 16, took part in the popular and violent overthrow of the dictator.

Romania was one of several stops of my two-week tour of the Balkans this month during which I sought to take the pulse of the region, which has been wracked recently by popular protests in several capitals. As luck would have it, I arrived in Budapest, my first stop, just in time to observe up close and personal the latest mass demonstration against Hungarian strongman and Trump bestie Viktor Orbán.

This was not my first experience with the region. As communist regimes in Eastern Europe were tumbling like dominoes from 1989 through 1991, I had a fascinating bird’s-eye view as the executive aide to the Assistant Secretary of European Affairs at the U.S. Department of State. In this position, I had access to all diplomatic and intelligence reporting, analyses and policy deliberations regarding Europe. Events moved so quickly, it was sometimes difficult to keep up. For example, I was the first to inform my boss and his senior staff that Ceaușescu had been overthrown. CNN had out-scooped our embassy in Bucharest.

Large crowds have been taking to the streets in Budapest, Bucharest, Belgrade, and Istanbul (as well as Tbilisi, Georgia) for months. They are discontented with their political leadership and demand change.

Serbia

On March 15, some 325,000 people took to the streets in Belgrade, Serbia’s largest demonstration ever. The proximate cause was a demand for accountability for the collapse last November of a new rail station in Serbia’s second largest city, Novi Sad, that killed 15 people. Protesters, led by students, charge that the catastrophe was the result of corrupt practices yielding shoddy construction. Taxi drivers, farmers, lawyers and military veterans joined the demonstration in large numbers. “We want institutions that do their jobs properly. We don’t care what party is in power. But we need a country that works, not one where you don’t get justice for more than four months,” a law student told the BBC.

The rail station tragedy was simply the spark that fired up resentment at more than a decade of governing by the Progressive Party’s President Alexander Vučić, who has occupied the top rungs of power since 2014. Young Serbs with whom I spoke complained of crony politics, rampant corruption and pro-Russia policies. One pointed to a complex of sleek new luxury apartment buildings and upscale shops on the outskirts of Belgrade financed by UAE billionaire investors and Russian oligarchs. With a broad wave of his hand, he said, “See all of this? It’s of the super-rich, for the super-rich and by the super-rich — with kickbacks to our politicians, many of whom, allegedly on government salaries, drive around in luxury automobiles and take their families on vacations to exclusive resorts abroad.”

A middle-aged woman likewise complained about the mysterious wealth of Serbian politicians. “They somehow manage to get rich while the rest of us just get by,” she said. While inflation is relatively low at 4.5 percent, youth unemployment, at close to 25 percent, is way too high, she added. Her grown children are finding it difficult to find employment commensurate with their university education. With that and the high cost of living, many adult children are compelled to live with their parents or emigrate, she complained.

Younger Serbs look to Brussels and the EU, not to Moscow, as do many older and rural folks, and they resent Vučić’s pro-Putin leanings. But, no matter who holds power, Kosovo is a key sticking point. A 2022 poll showed that 75 percent of Serbs would not support Kosovo’s independence for the sake of Serbia’s faster entry into the EU, 16 percent would support it, with nine percent undecided. The present attitude therefore is one of “no solution is a solution” resulting in Belgrade’s remaining outside of mainstream Europe indefinitely.

Serbs have been turning out steadily to protest against their government. My contacts indicated they will continue unabated.

Romania

Romania has been rocked by political tensions and demonstrations, some violent, since the country’s Constitutional Court disqualified an obscure figure, Moscow-backed ultranationalist Călin Georgescu, from running in upcoming May presidential elections after he came out ahead in a first-round vote last November; the court did so on grounds of Russian meddling. Fed up with corruption and politics-as-usual, Many Romanians, primarily in small cities and rural areas, are following the familiar populist path. The trouble is, another far-right politician, George Simion, has thrown his hat in and enjoys growing support. Should he succeed in attracting Georgescu’s voters, it could result in yet another central European country moving closer to Moscow in the footsteps of Hungary and Slovakia. This makes EU leaders very nervous and would further weaken NATO.

Ordinary Romanians related to me a line I’ve heard countless times in the U.S: “One side says one thing. The other side says another. I don’t know what to believe.” These same people also feel Georgescu was framed. To muddy the situation further, Elon Musk and J. D. Vance have both meddled in Romania’s politics, backing Georgescu.

Romania, as did the U.S. before Trump returned to office, has experienced positive economic indicators, notching a high growth rate and relatively low unemployment and inflation.

Romania was the sole East Bloc country to shake off communist rule via widespread violence and to have executed its leader. I asked Egmont Puşcaşu about this. He unconvincingly explained that Ceaușescu was a communist killed by communists in accordance with their unjust way of exercising power. While he as a young man could justify the way Romania’s dictator was dispatched, he could not today. As tensions mount in the lead-up to next month’s election, violence cannot be ruled out. And should a far-right, pro-Russia candidate win, all bets are off in terms of European security.

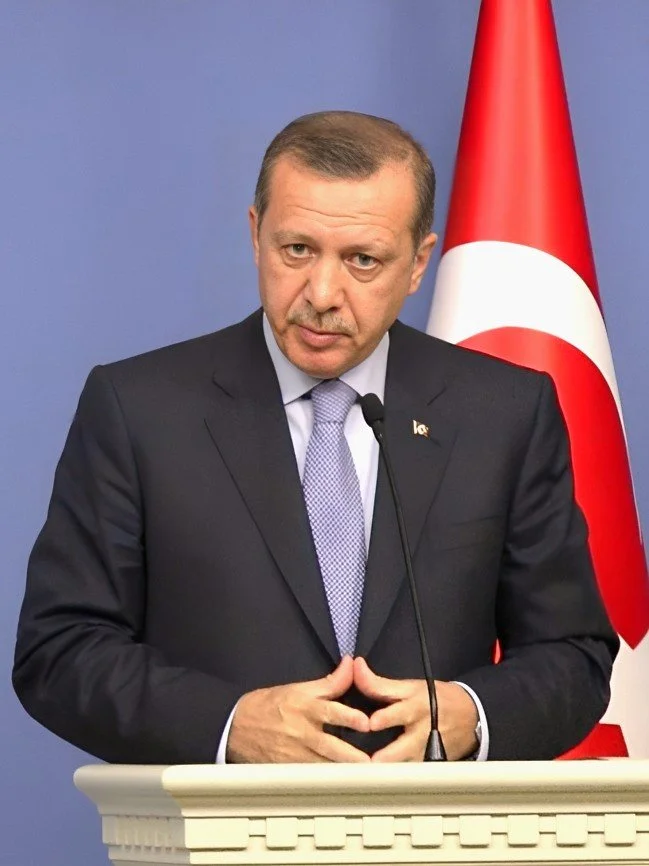

Turkey

Turkey has been wracked by a series of mass pro-democracy protests since the March 19 arrest of Istanbul’s popular mayor Ekrem Imamoglu on corruption and terrorism charges, an act viewed by human rights organizations and many Turks and as politically motivated. Two-thousand were arrested. Hundreds of thousands turned out in Istanbul’s streets again ten days later to protest his arrest in what was the country’s largest demonstration in a decade.

While the protests have been led by Imamoglu’s Republican People’s Party (CHP) and students, they have also drawn from a wide cross-section of Turkish society, including far-right nationalists and Kurds — groups that rarely see eye-to-eye politically.

They are united by a wariness with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan 20-year, increasingly authoritarian rule and his retreating from modern Turkey’s founder Mustafa Atatürk’s principles, notably secularism. As in Hungary and Serbia, Imamoglu’s arrest was the spark that set the tinderbox of many other grievances afire. While Turkey’s GDP growth has been fairly strong, inflation is at a withering 39 percent and youth unemployment stands at 15 percent.

Young people with whom I spoke complained about the steep cost of living, housing unaffordability, immigration and Erdogan’s authoritarianism. On immigration, specifically, those in Istanbul (population 22 million) resent the thousands of Russian draft evaders and oligarchs whose snatching up of properties has contributed to rising rents and real estate values. In addition, more than 3 million Syrian refugees reside in Turkey, placing more stress on government services.

The recent protests may mark a pivotal moment for Turkey. Erdoğan, 71, is rumored to have health problems. Turks are becoming restive, eager to move on with new, younger leaders. Imamoglu, 53, progressive and a committed secularist, is very popular, particularly among youth. Even more popular in the polls is Ankara mayor Mansur Yavaş, 69, a pragmatist noted for being corruption-free and getting things done.

With a population of over 85 million, the world’s 17th largest economy and its strategic location, Turkey warrants close watching. Should Turks choose to change course away from Erdoğan’s creeping authoritarianism to reclaim full democratic norms and secularism, it would present an example for Americans to follow.

Wither the Balkans?

A statement, often attributed to Winston Churchill, goes, “The Balkans produce more history than they can consume.” In recent times, this was borne out in the Balkan Wars preceding World War I, that war itself ignited in the Balkans, the break-up of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires, World War II Balkan battlegrounds, Cold War communist rule, the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1992 and the subsequent decade-long bloody Yugoslav Wars ending in 2001.

The region is again restive. Recurrent mass demonstrations in Balkan cities reflect a growing discontent with the elites and a yearning for change, spearheaded by young people. Whether change goes in a positive or negative direction is too soon to tell. All of the Balkan nations, with the exception of Slovenia, are losing population as a result of declining fertility and emigration, which poses political and economic challenges for the future. All but Slovenia, in fact, are in “demographic crisis,” according to experts. It is an open question whether the autocratic political structures wrought by strongmen Orbán and Erdoğan are sustainable, or are merely passing phenomena. That goes as well for Serbia’s wily Vučić.

Where go the Balkan countries could also portend where goes the United States, which is witnessing its own home-grown mass demonstrations against the Trump-Musk policies. But it is the absence of American influence under Trump that bodes ill for all of Eastern Europe. Strategic withdrawal combined with brainless destruction of the federal government and a treasonous policy alignment with Vladimir Putin render Eastern Europe vulnerable to Russian aggression. One therefore cannot rule out the region again being engulfed in flames.

In the small village of Cazenovia, NY, where I settled with my family after leaving the Foreign Service, is buried Charles Homer Haskins, one of three expert-advisors who accompanied President Woodrow Wilson to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 to negotiate the peace terms ending World War I. A medievalist by training, Haskins helped redraw the map of Europe out of which emerged today’s Central European, Eastern European and Middle East nations — though six of them were folded into the historically ephemeral entity called Yugoslavia. For this he was awarded France’s Légion d’Honneur, Belgium’s Ordre de la Couronne and a host of other honors. Borders readjusted themselves over the decades through conflict. I’m sure Haskins and his colleagues thought they did their best, though Hungarians and Romanians, Serbs and Albanians and Bosnians, Kurds and Turks and Iraqis would disagree. The upshot is this: the Balkans, ethnically and geographically, were tailor-made for turmoil, another period of which we may be entering..

James Bruno (@JamesLBruno) served as a diplomat with the U.S. State Department for 23 years and is currently a member of the Diplomatic Readiness Reserve. An author and journalist, Bruno has been featured on CNN, NBC’s Today Show, Fox News, Sirius XM Radio, The Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Huffington Post, and other national and international media.

The opinions and characterizations in this article are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent official positions of the U.S. government.