On TV, Political Ads Are Regulated – But Online, Anything Goes Ari Lightman

With the 2020 election just a year away, Facebook is under fire from presidential candidates, lawmakers, civil rights groups and even its own employees to provide more transparency on political ads and potentially stop running them altogether.

Meanwhile, Twitter has announced that it will not allow any political ads on its platform.

Modern-day online ads use sophisticated tools to promote political agendas with a high degree of specificity.

I have closely studied how information propagates through social channels and its impact on political messaging and advertising.

Looking back at the history of mass media and political ads in the national narrative, I think it’s important to focus on how TV advertising, which is monitored by the FCC, differs fundamentally with the world of social media.

The birth of political ads

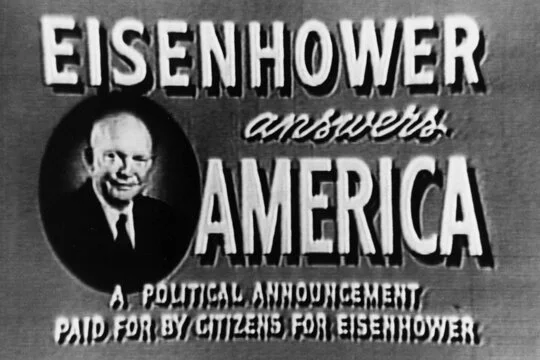

Eisenhower was one of the first politicians to use TV as a medium to spread his message to the American public.

In 1952, Eisenhower met with Rosser Reeves, an American ad executive, to discuss how to use this relatively new medium. They created 20- to 30-second slots to run during prime-time, called “Eisenhower Answers America.”

These ads helped usher in how political campaigns would use new broadcast media to campaign.

TV ads were also used in the campaigns of Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon in the 1960s to shock viewers into going to the polls by catering to their fears of a world that might exist should their opponent win.

Over time, TV ads became more negative and critical of opponents’ ideology and positions. For example, in the late 1980s, George H.W. Bush attacked Michael Dukakis on his prison furlough program giving weekend passes to convicted criminals. They used convicted felon Willie Horton to provide added emphasis and provoke fear-mongering.

From TV to Twitter

To understand how effective their ads have been, TV advertisers use measures of reach and frequency of views. These measures are based on a general understanding of the type of viewers that might be watching a given channel, show and time slot.

However, it’s hard to understand a given ad’s effectiveness in driving voters, especially as modern TV audiences migrate to video on demand and other streaming platforms.

In other words, TV political advertising today might provide highly skewed results based on demographics. That’s because the people who still watch live broadcast TV tend to be older than the average American.

With the advent of the web, political messaging went online. First, there were websites focusing on the campaign; then, videos on platforms like YouTube to show support for candidates; and now, political ads use social networks to campaign, create community and raise money.

Unlike TV, social networks offer the ability to hyper-target individuals by characteristics like geography, age and interests. They provide real-time measurable outcomes while rapidly disseminating political messages.

There is also the issue of cost. For example, a 30-second advertisement during the popular TV show “This is Us” cost about US$434,000 last year. Facebook political ads can run for a fraction of that cost and be much more effective at reaching specific audiences, due to targeting.

With a plethora of data on what drives people to click, share or pledge money, modern-day political strategists can now understand what messages help reinforce their base and slowly percolate them into the consciousness of those who might be swayed.

Hyper-targeting and tailoring messaging for individual users can reinforce a person’s deeply held beliefs. It also contributes to the spread of disinformation. This is a more fundamental issue than simply focusing on whether an ad is truthful or not

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook (Al Drago/Getty)

The regulation gap

One of the other big differences between social network political ads and TV ads is the impact of regulation.

TV is regulated by the FCC, while social networks are self-regulated.

The FCC was established by Franklin Roosevelt with the assumption that the airwaves belonged to the people. With the growing popularity of TV in the 1950s, the FCC regulated obscene and indecent material. It also set out to ensure there would be balance and truth associated with political messaging.

FCC regulations stipulate that broadcasters must allow any qualified candidates for political office the opportunity to purchase an equal amount of advertising time at the lowest unit charge.

In addition, regulations required transparency from political groups running the ads, which includes mentioning in the ad the name of the group purchasing the commercial time, and whether the advertisement is part of the candidate’s campaign efforts, or if another political action group paid for the spot.

In contrast, without regulation, political ads on social networks can hide behind a cloak of secrecy. The Federal Elections Commission does provide guidance on advertising and disclaimers on any public communication made by a political committee – requiring, for example, statements such as “My name is [Candidate Name]. I am running for [office sought], and I approved this message.”

However, Katherine Haenschen, an assistant professor of communication at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, found that Google and Facebook often requested and received exemptions from requiring advertisers to include standard disclaimers.

Facebook recently decided on its own to require disclosures from advertisers when they purchased political ads, including the organization’s government-issued identification number.

However, social networks like Facebook will have a difficult time providing complete transparency on why members might be seeing a particular political ad. Financially, it is not in their best interest to do so. This is reflected in the company’s recent stance toward several petitions against posting false political ads on the network.

What the future holds

I think the future of political ads on social networks involves greater levels of checks and balances.

In my view, the networks’ efforts on self-regulation and transparency are steps in the right direction.

Senators Amy Klobuchar, Lindsey Graham and Mark Warner have proposed the Honest Ads Act, which would force online political advertising to adhere to the same stipulations as political ads on TV.

Independent media outlets, like ProPublica, are also taking steps to inform the public about the power of targeted political messaging.

However, the size and scope of the problem of political disinformation and hyper-targeting in social networks still needs to be addressed. This is simply too powerful for political campaigns and political operatives not to exploit. I fear that it will invariably lead to greater manipulation of public opinion in the runup to the 2020 campaign.

Ari Lightman is Professor of Digital Media and Marketing at Carnegie Mellon University

This article originated at The Conversation