Reflections on Russia 100 Years After the Russian Revolution: Part I By Nathan Richmond

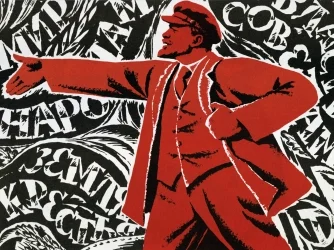

November 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, an event of immense historical importance. The centenary of the Revolution is a good opportunity to pause and reflect on Russia’s past, present, and future.

The Importance of Thinking Like a Russian

The most important concept that I have learned in more than 40 years of Russia-watching is that in order to understand Russia, it is necessary to think like a Russian. This is very difficult, often impossible for Americans, because we have a completely different mindset. If I had to compare the American and Russian mindsets in three key words they would be as follows: Americans are individualistic, optimistic, and superficial. Russians, on the other hand, are collectivist, pessimistic, and deep (deep in the philosophic sense- profound).

These are, of course, generalizations and don’t apply to everyone in either country. But in general, it has been my observation that Russians, especially the older generation, are very conservative, very religious, bordering on superstitious, fatalistic, very suspicious of others’ motives, and generally, not risk takers.

There is a Russian proverb that captures the importance of not taking risks: “The tallest tree gets cut down first.” Thus, don’t stick your neck out, don’t stand out from the crowd, to call attention to yourself, or you will put yourself at risk.

They have another saying that I think also illustrates the Russian mindset: “An optimist is an uninformed pessimist.” In other words, if you knew what I know, you would be pessimistic also.

So in order to understand Russia, we need to try to see their lives, their country, and the world through their eyes. Without doing so, we will forever be at a loss to understand why they do the things they do.

Russia’s Past

When thinking about Russia over the course of the last 100 years there are four things that stand out to me:

1) Since the Revolution the least expected among the leaders has usually emerged as new leader.

Prior to the Revolution, Russia was a monarchy, and there was an order of succession that was hereditary. For about 300 years, from 1613 to 1917, the Romanov Dynasty ruled Russia and the crown (usually) passed from father to son or from brother to brother. With the overthrow of the Provisional Government in November 1917 and the subsequent establishment of a Communist government, Russian leaders paid scant attention to the issue of leadership succession. This was probably due, in part, to their Marxist belief in the “withering away of the state” which would abrogate the need for elites, political succession, etc.

Gravely ill following a series of strokes in the early 1920s, Lenin dictated his “Testament,” a candid assessment of Russia’s other leaders. Lenin’s illness and subsequent death in 1924 began a succession struggle that played out over the course of several years, culminating with Stalin, an uneducated, brooding, paranoid introvert whom the other leaders looked at with contempt, and the least likely among the inner circle of leaders to assume control, consolidating his power by the late 1920s.

This pattern was repeated following Stalin’s death in 1953 with Khrushchev, a flamboyant peasant whom the other leaders considered to be a clown, consolidating his power a few years later. Brezhnev, a dull, colorless figure who had been demoted during Khrushchev’s rule, managed to vanquish his rivals and consolidate power a number of years following Khrushchev’s 1964 overthrow.

Yeltsin, a flamboyant, hot-tempered, outspoken, crusading anti-corruption politician who was purged from Gorbachev’s inner circle, managed a remarkable political comeback and succeeded Gorbachev following the collapse of the USSR in 1991. And finally, Putin’s becoming Russia’s president following Yeltsin’s surprise resignation on the last day of 1999 culminated his improbable rise from KGB operative to the pinnacle of Russian power. In each of these examples, the least expected person ultimately assumed power.

Alexei Nikoskyi/Reuters

2) In the absence of free, fair, and meaningful elections, new leaders always attempt to justify and legitimize their rule by repudiating the prior leader’s policies and trying to enhance Russia’s global role.

No longer a monarchy, yet absent free, fair, and meaningful elections, Soviet and post-Soviet leaders attempted to legitimize their rule by repudiating the prior leader’s policies and by trying to enhance Russia’s global role. Hence, despite his claims of continuing Lenin’s policies, Stalin’s “Socialism in One Country” policy was a sharp reversal of Lenin’s commitment to world revolution. Khrushchev’s policy of “de-Stalinization” was an abrupt reversal of Stalin’s policies and legacy.

Brezhnev implemented “de-Khrushchevization” and “re-Stalininzed” the USSR, albeit on a limited basis. Gorbachev repudiated Brezhnev’s policies of “stability” and “mature socialism” condemning Brezhnev’s era as one of “stagnation” and instead embraced dynamic change in the form of perestroika. Following the collapse of the USSR, Yeltsin deemed Gorbachev too timid and implemented radical political, economic, and social changes for nearly a decade, until Putin assumed power and reversed most of Yeltsin’s policies.

Every leader in the post-Tsarist era, (with the exception of Andropov and Chernenko who each governed for about a year and thus whose leadership was too brief to fully consider) has successfully staked their claim to leadership on the basis of sharply repudiating, sometimes in action only, other times by word and deed, their predecessor’s policies.

3) The “good old days” for Russians was during the USSR, especially in the post-WW II and post-Stalin eras, but that doesn’t mean they want to recreate the USSR today.

When Russians think about their country’s past, their version of “the good old days” is the USSR. Recognizing that not everything was perfect during the Soviet era, they often speak of their country’s past in terms of their “mountains of accomplishments” that were accomplished at the expense of “mountains of crimes.” The “mountains of accomplishments” refers to the rapid industrialization and near-universal education of their society, their improbable defeat of Nazi Germany, and their post-WW II superpower status. But rapid industrialization and their other accomplishments came at a very high cost in terms of human lives: the purges, the collectivization of agriculture and ensuing famines, the forced paced industrialization and the military victory of Germany cost in total millions of lives.

At the last census conducted in the USSR in the 1989, the total population was a little less than 300 million. But under normal circumstances, absent war, revolution, and the other variables I mentioned, their population should have been about 450 million. More than one hundred and fifty million either met premature deaths or were never born under these circumstances. The political repression that touched nearly every family, the economic mismanagement, and the poor strategy before and during WW II constituted the “mountain of crimes”.

President Putin has described the 1991 collapse of the USSR as “the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the Twentieth Century”, and a vast majority of Russians probably would agree. But this does not mean that Putin, other leaders, or Russians in general have any appetite to try to recreate the USSR. At a minimum, they probably want to exercise power in the “Near Abroad,” their traditional sphere of interest, including the Baltics, Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. At most, some leaders would favor a union of Slavic nations including Belarus, Ukraine, parts of Moldova and parts of Georgia, and Kazakhstan along with exercising power in their traditional sphere of interest including the Baltics, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.

4) The “bad old days" was the decade following the USSR’s collapse, and any repetition of that era is to be avoided.

When Russians think of their country’s past and “the “bad old days” they are referring to the decade following the collapse of the USSR. Yeltsin’s attempt at radical economic reform, dubbed “shock therapy” resulted in hyperinflation that wiped out the life savings of many, and impoverished Russia to the point where it depended on the West for foreign aid. This was a blow to Russians not only in terms of their physical standard of living, but also was a psychological blow to Russians who took pride in their country’s position as a superpower.

Russia’s prominent role on the global stage was one of the sources of legitimacy of Soviet and Russian rulers throughout the Twentieth Century. Under Yeltsin, Russia was reduced to begging from the West and was humiliated by the expansion of NATO to Russia’s former allies and even included some former Soviet republics. Righting the Russian ship of state by reversing many of Yeltsin’s policies would become priorities for President Putin and his allies and supporters at the turn of the Twenty-first Century.

The next part of this analysis will assess the contemporary state of Russian politics and future prospects.

Nathan Richmond is Professor of Government at Utica College