Guilt of a Meritocrat: The Need to Expand the American Dream By James Bruno

The actress Felicity Huffman was sentenced today after having been convicted of paying a $15,000 bribe to have her daughter's SAT score raised to enhance her chances of getting into an elite university. Her punishment: fourteen days in prison, a $30,000 fine, 250 hours of community service and one year supervised release. Huffman is the first of 33 parents, who paid $25 million in bribes, to be sentenced.

The college admissions scandal underscores a decades-long trend in the United States of the growing gap in wealth and opportunity between an educated, moneyed elite and everyone else. New York Times columnist David Brooks describes these elites:

Exclusive meritocracy exists at the super-elite universities and at the industries that draw the bulk of their employees from them... Whether it’s the resort town you vacation in or the private school you send your kids to, exclusivity is the pervasive ethos. The more the exclusivity, the thicker will be the coating of P.C. progressivism to show that we’re all good people.

And J.D. Vance makes the point in his brilliant book, Hillbilly Elegy, which chronicles his own trajectory from working class to professional elite, that ascending to America's upper class is not merely a factor of money and education:

Social mobility isn’t just about money and economics, it’s about a lifestyle change. The wealthy and the powerful aren’t just wealthy and powerful; they follow a different set of norms and mores. When you go from working-class to professional-class, almost everything about your old life becomes unfashionable at best or unhealthy at worst.

He elaborates further on what it takes to get ahead in today's America:

Successful people are playing an entirely different game. They don’t flood the job market with résumés, hoping that some employer will grace them with an interview. They network. They email a friend of a friend to make sure their name gets the look it deserves. They have their uncles call old college buddies. They have their school’s career service office set up interviews months in advance on their behalf. They have parents tell them how to dress, what to say, and whom to schmooze.

This is confirmed by Al Lubrano in his book, Limbo: Blue Collar Roots, White Collar Dreams:

'Because it's part of their class consciousness, second- and third-generation college students know how to manage their time, how to figure out what to focus on, and how to work their way through' - with a boost from their parents.

Lubrano, like Vance, is a straddler from blue collar to white collar class - both also first generation in their families to go to university, Ivies at that. Lubrano makes the point that being a member of America's elite classes is a factor more of educational level than of income.

I find myself, as a straddler, facing my own class quandary - vis-a-vis my children and my nation.

I've written previously in this blog of my own journey as a first generation college grad, my father not having completed high school, his mother illiterate. The eyes of my classmates (at GWU and Columbia) widened when I told them that a regular family Sunday pastime was to cruise the fields to see how the crops were doing; about my quasi-Dickensian education replete with beatings and dunce stools; shooting guns for fun; getting into a fist fight in ninth grade geography class; and my sweet girlfriend who was the county dairy princess. My college classmates spent their summers bumming in Europe or as unpaid interns with big city organizations. I returned to classes sunburnt from a summer of working on heavy construction (always with Foreign Affairs Magazine on the seat of my dump truck!). I related some of this background to the examiners during my Foreign Service oral test. Their eyes also widened.

Here's my dilemma. I'm an Ivy grad who's had a great professional career, married to a European equivalent. Our kids are the beneficiaries of tons of what sociologists call "cultural capital." Whereas I was utterly clueless as to how to make it in elite education and professions and struggled as a result, my kids know. Mom and Dad have bequeathed a wealth of knowledge and tips on what it takes to navigate this world that was so alien to me. Unlike when I was their age, they know how to network, to speak the coded language of the educated "meritocracy," to master the body language and cultural milieu in which we swim. Mom and Dad helped steer them through the college application process. Mom, herself a university instructor, was a croesus of insider information. We paid for tutors and repeat sittings for the SAT and ACT. With a phone call, we can arrange introductions for internships. Both kids landed fat merit scholarships. Both are smart, self-motivated, grounded.

David Brooks addresses this inherited leg-up of the professional classes:

Parents in the exclusive meritocracy raise their kids to be fit fighters within it... (But) the exclusive meritocracy is spinning out of control. If the country doesn’t radically expand its institutions and open access to its bounty, the U.S. will continue to rip apart.

And that's the crux of my dilemma. The key difference between us and Felicity Huffman and her fellow bribers is that we don't break the law. But we share space in the "meritocratic" class of educated, professional elites. We're hogging the American Dream. We've got ours, Jack. But what are we doing to assist the Me's of yesteryear?

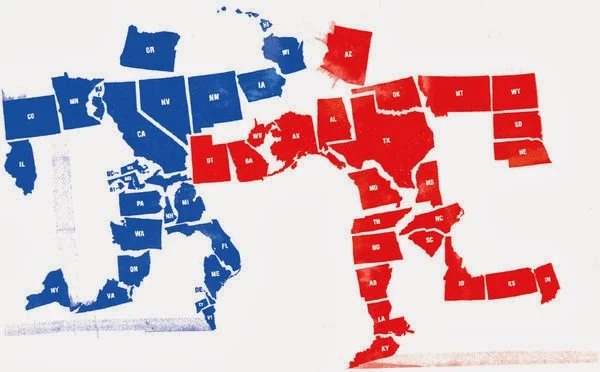

I recently wrote about this in Washington Monthly, The Lessons of Theodore Roosevelt, in which I address the growing wealth gap and the dangers it poses for the nation: "by manipulating the tax and legal systems to their benefit, America’s most educated elite, the so-called meritocracy, have built a moat that excludes the working poor, limiting their upward mobility and increasing their sense of alienation, which then gives rise to the populist streak that allowed politicians like Trump to captivate enough of the American electorate."

There are economic measures we need to take urgently, such as raising taxes on the rich and devoting more resources to enhancing training and job opportunities for people who work in the trades. But more is needed.

J.D. Vance offers some moral advice: "One way our upper class can promote upward mobility is not only by pushing wise public policies but by opening their hearts and minds to the newcomers who don’t quite belong."

Those of us who have succeeded in the so-called meritocracy need to think hard and act on this - initially at the ballot box. If we don't, we can watch the steady eclipse of the American Experiment as we tweak our IRA's and 401(k)'s.

James Bruno (@JamesLBruno) served as a diplomat with the U.S. State Department for 23 years and is currently a member of the Diplomatic Readiness Reserve. An author and journalist, Bruno has been featured on CNN, NBC’s Today Show, Fox News, Sirius XM Radio, The Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Huffington Post, and other national and international media.