Doug Jones Turns Alabama Blue in Special Election By Heather E. Yates

The last of the special elections concluded on Tuesday evening in Alabama with Doug Jones achieving an upset victory making him the first Democrat elected to the Senate from that state since 1996. The year’s special elections converted many of the country’s deeply Republican refuges into the unlikeliest battlegrounds.

Doug Jones was considerably competitive for a Democrat in the South, which was remarkable in a state where President Trump and the ranking Senator Richard Shelby (R) both won by a 28-point margin. Moore led Jones in the polls with a consistent and comfortable lead until allegations of sexual assault became public a month ahead of the election.

It was only then Doug Jones tied with Roy Moore according to the RCP poll average at 46 percent. Moore rallied and closed the gap two days before Tuesday’s election with a 3.7 point lead over Jones. The final polling data compiled at RCP on the eve of the election favored Roy Moore, but within the margin of error. Doug Jones won by over one percent.

Jonathan Bachman/Reuters

What does the Doug Jones victory mean for Democrats?

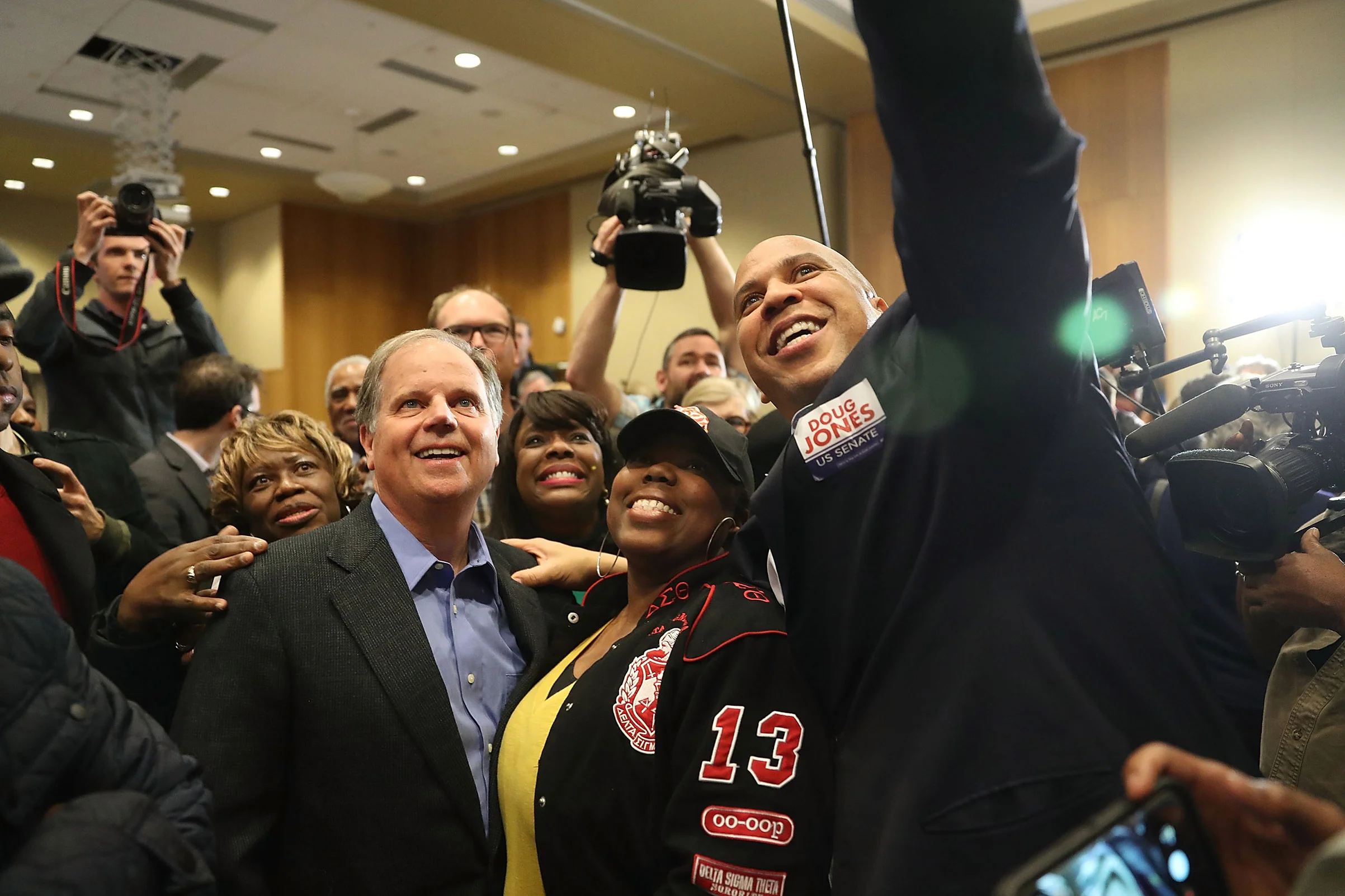

Money and mobilization matter, campaigns matters, issues are important, and voters are listening. Doug Jones was assisted with a massive coordinated mobilization apparatus deployed on the ground in Alabama. A compilation of national grass-roots organization that partnered with local chapter groups like the NAACP. The turnout of African-American voters in Alabama cannot be overstated. 29 percent Black voter turnout, and Black women in particular, is credited with delivering the victory for Doug Jones.

The ground operation was well organized and well funded. The conventional norms still enlisted the help of the Party’s elite headliners including Barack Obama and Joe Biden who recorded robo-calls. Campaign events featuring Senator Cory Booker, Representative John Lewis, and athlete Charles Barkley were particularly important for drawing attention to what was at stake in this election.

Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty

For candidates, money in campaigns buys access to airwaves and mailboxes, and supports get-out-the-vote efforts. The role of money in the Alabama campaign was particularly compelling because Doug Jones out raised Roy Moore with an impressive $10.2 million in contrast to Moore’s $1.8 million.

Super PACs were very active on both campaigns, albeit, in different ways. A Washington D.C. based super PAC titled Highway 31 contributed approximately 40 percent of Jones’ total war chest and assisted Jones’ campaign’s air war against Moore. The Pro-Trump group America First Policies and the Club for Conservatives PAC supported Moore with in-kind donations of polling services and targeted messaging. For Jones, the role of money in his campaign assisted a massive mobilization effort to counteract the partisan advantage Moore had in Alabama. The special election reinforces the notion that campaigns matter.

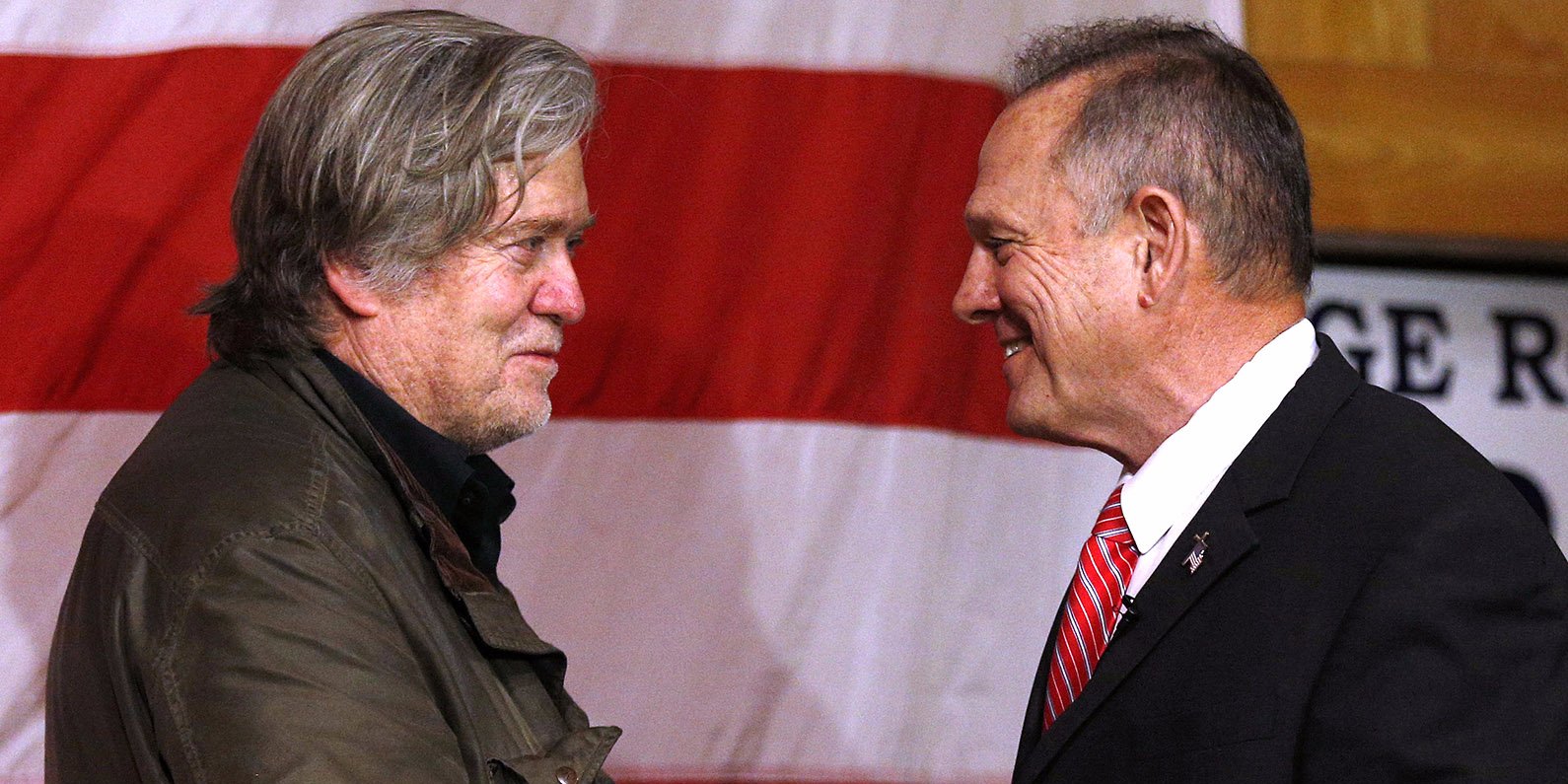

Further complicating the matter for the Republicans is the internal ambivalence displayed towards how to support deeply flawed candidates. The conflict in Alabama was easily reduced to a choice between the balance of power in the U.S. Senate (which meant protecting a deeply flawed candidate) and a standard of ethics.

Many Republican leaders and elite donors had withdrawn its support from Moore once the allegations were public, but the Party was thrust into an awkward limbo when President Trump fully endorsed Moore’s candidacy a week ahead of the election, which seemingly cued the RNC to reinstate its support and exacerbated internal discord among the rank-and-file members.

Although Roy Moore enjoyed a perceived partisan advantage on the ground, he was a scandal-ridden candidate with deep flaws, which notably reprised some of the Republican Party’s familiar fractures. The Doug Jones victory in Alabama also conveys what some Republican leaders already understand, the scorched-earth political strategy does not translate into electoral victories for the Party. It delivers more liability than results. Although it plays well with small pockets of voters situated in deeply red districts, it also repels the median voter whom the Republican Party cannot afford to forego heading into the 2018 midterms.

Heather E. Yates (@heatheryatesphd) is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Central Arkansas and the author of The Politics of Emotions, Candidates, and Choices (Palgrave).