How the 2016 presidential election influenced the 2020 Democratic Primary By Luke Perry

The Utica College Center for Public Affairs and Election Research partners with Palgrave-MacMillan to produce the book series Palgrave Studies in U.S. Elections. The series recently published a new book The 2020 Democratic Primary: Key Developments, Dynamics, and Lessons for 2024. The following is an excerpt from Chapter One.

The 2016 presidential election process and outcome cast a long shadow on 2020. A relatively large number of candidates often run when there is not an incumbent president. This was particularly the case for Republicans in 2016. Twenty candidates vied for both party nominations in 2016, 15 of whom remained viable into the primaries. Donald Trump emerged from a dozen GOP candidates, Hillary Clinton was one of three. These numbers were higher than average for Republicans, smaller for Democrats, “but not substantially out of the ordinary in either ease.” Most primary races over the past forty years included at least six candidates, though this number has varied, as have previous open-seat elections in 2008 (16), 2000 (8), and 1988 (14). Donald Trump was one of three candidates with no previous political experience, a rarity. Over two-thirds of presidential candidates in recent decades previously served as president, vice-president, senator or governor. 1 in 8 were House members (Aldrich et. al. 2019, 19-22).

Trump’s general election victory was surprising on multiple fronts. Trump consistently trailed in the polls, while four years earlier, “more than a loss, the primary election battle and Mitt Romney’s subsequent performance suggested serious concerns about the Republican Party’s long-term potential to reach citizens in the new American electorate.” There were signs that Trump might be different. He was “seriously considered” as “a legitimate candidate” in 2012, briefly polling as the Republican favorite, “spearheaded by his obsession with Barack Obama’s birth certificate” (Miller 2013, 11-15).

Obama’s landslide victory in 2008 “shook the political order” with “a populist message and charismatic delivery that beckoned comparisons to past revered Democratic leaders Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy. Seven months later; however, Obama’s approval fell from 65 percent upon taking office below 50 percent as “voters became dissatisfied when their situations did not improve significantly” within a gradual and uneven recovery from the Great Recession (Miller 2013, 2). Meanwhile, the Tea Party, a new faction within the Republican Party beginning in 2009, became a major force in electoral politics, particularly in the 2010 midterm, and party politics.

Business conservatives, Tea Party members, and evangelical Christians “each had a chosen candidate” in the 2012 primary, which “led to speculation on whether the GOP would come together in November or not.” They did, but “Republicans were not enthusiastic about Romney’s candidacy” (Miller 2013, 12-17). Four years later, Trump ended a “string of presidential contests featuring mainstream candidates from both parties.” Trump’s “rise to the top in the face of nearly unanimous opposition from Republican leaders, donors, and pundits, not only exposed deep fissures within the party, but also threatened to disrupt and perhaps reshape the current national party alliance.” Trump emerged in a political climate with increased polarization between both parties, among leaders and voters, who “sorted themselves into increasingly distinct and discordant political camps” that disagreed on a wide array of issues and viewed political opposition with increased distrust and disdain (Jacobson 2016, 226-8).

Photo from President Obama’s presidential library

In 2016, “fundamental predictors of election outcomes did not clearly favor either side” (Sides et. al. 2016, 50). At the time, racial diversification of the electorate was viewed as “favorable to Democrats,” but increased entanglement of racial and political identities during the Obama presidency helped develop Trump’s conservative base, who narrowly propelled him to an upset victory. Trump’s 57 percent Electoral College vote share was historically narrow (46th out of 58 elections), while his popular vote total margin (-2.1 percent) was the third lowest (Patel & Andrews 2016).

Trump’s unexpected success created extraordinary internal tension for Democrats. The 2020 Democratic primary was largely defined by “the party’s conversations and fights about the previous election,” explained in Learning from Loss, as Democrats “struggled to come up with a reason why Hillary Clinton had lost to Donald Trump” (Masket 2020, 3). Their inability to agree on a narrative made it more difficult than usual to select their nominee in 2020. Making matters worse, 2016 was so close that several explanations of defeat could be correct.

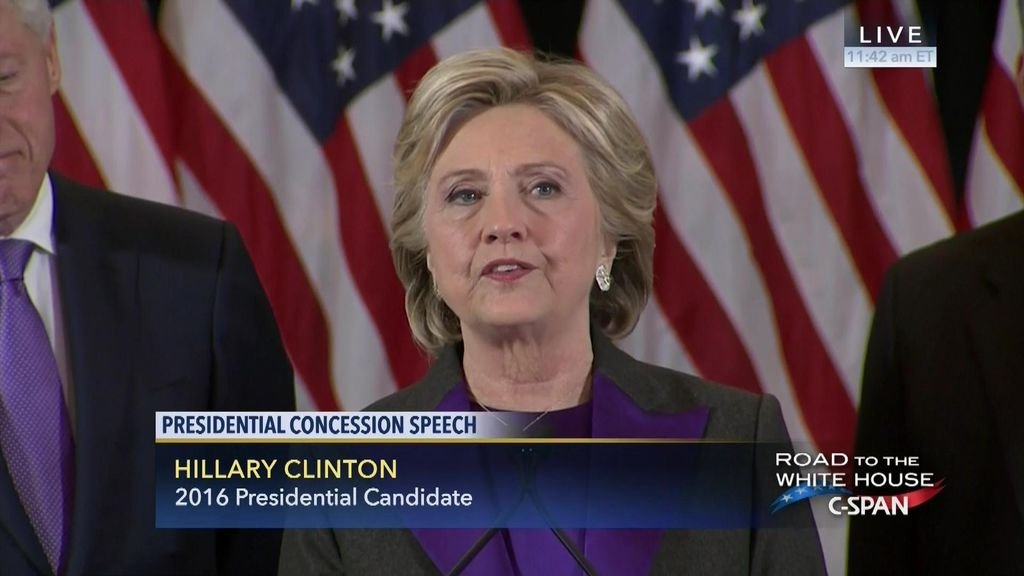

Photo from CSPAN

Interviews with Democratic Party activists conducted by Seth Masket between 2017 and 2020 produced eight different narratives for understanding Trump’s victory. Four narratives focused on the candidacy of Hillary Clinton: 1) campaign activity, 2) campaign messaging, 3) candidate traits, and 4) identity politics. Clinton was a poor candidate with inadequate campaign tactics and insufficient messaging that spoke to women and racial minorities, but failed to resonate with low income white people. The other four narratives involved external factors: 1) racism/sexism, 2) Bernie Sanders/Jill Stein, 3) exogenous events, and 4) mood of the electorate. Clinton was hindered by sexism, other Democratic candidates drawing support, Russian interference, actions by FBI Director James Comey prior to the election, and an electorate open to change after eight years of a Democratic presidency.

Democratic activists often cited multiple explanations. Narratives focused on Clinton’s campaign and candidacy clearly outnumbered narratives focused on external factors, but activists were divided by candidate preference and gender. Clinton’s supporters more frequently cited external factors, while Sanders’ supporters blamed Clinton. Men were much more likely to criticize Clinton’s campaign than women, who were far more likely to blame outside events and sexism. Masket noted how infrequently the topics of Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Vice-Presidential candidates, and the Electoral College arose, plus much of what presidential election forecasts in Political Science typically focus on. “In a period of good-but-not-amazing economic growth, relative peace abroad, and the incumbent party seeking a third term in office, you’re going to see a competitive race,” Masket explained. “The idea that Hillary Clinton should have won this election and somehow blew it isn’t really supported by the available evidence” (Masket 86-87).

The range of explanations for 2016 grew over time, prompting more disagreement just a few years later than immediately after the election. Moreover, levels of support for various narratives shifted. Critiques of Clinton’s campaign tactics and candidacy became less frequent, while attributing blame to exogenous events, Bernie Sanders, and sexism/racism became more prevalent. As the 2020 primary unfolded, preferred explanations of 2016 correlated with support for different candidates. Joe Biden was the top choice of activists who believed messaging, candidate traits, identity politics. Elizabeth Warren was the top choice for activists who pointed to exogenous factors and the mood of voters. Bernie Sanders was the top choice for activists who blamed Clinton’s campaign. As a result, no consensus view emerged over 2016 and what that meant for selecting a nominee in 2020. Instead, Democrats grew more divided over this question.

The challenge for Democrats in 2020 was that the primary system “does not automatically produce nominees who are capable of doing well in the November election” (Geer 1986, 1007). “Factional candidates may skillfully parlay narrow but intense support into a party nomination, or party regulars, who lack appeal to independents, may sweep to victory.” The nomination system works best “when voters and party professionals work in partnership.” When this fails to happen, “both major political parties are at risk of producing nominees who aren’t competent to governed and/or don’t represent a majority of the party’s voters.” (LaRaja & Rauch 2020) . . . For more click here.

Luke Perry is Professor of Political Science at Utica College

Aldrich, John, Jamie Carson, Brad Gomez, and David Rhode. 2019. Change and Continuity in the 2016 and the 2018 Elections. New York: CQ Press.

Geer, John. 1986. Rules Governing Presidential Primaries. Journal of Politics 48, no. 4: 1006-1025.

Jacobson, Gary. 2016. Polarization, Gridlock, and Presidential Campaign Politics in 2016. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667: 226-246.

LaRaja, Raymond and Jonathan Rauch. 2020. “Voters Need Help: How Party Insiders Can Make Presidential Primaries Safer, Faier, and More Democratic.” Brookings, January 21, 2020.

Masket, Seth. 2020. Learning from Loss: The Democrats (2016-2020). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, William. 2013. “The 2012 Republican Nomination Season: A Clown Car of Feuding Conservatives?” in The 20212 Nomination and the Future of the Republican Party, edited by William Miller. Lantham, MD: Lexington Books.

Patel, Jugal and William Andrews. 2016. “Trump’s Electoral College Victory Ranks 46th in 58 Elections.” The New York Times. December 18, 2016.

Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2016. The Electoral Landscape of 2016. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667:50-71.