Recent Racist Attacks at Syracuse University Are Rooted In The Black Student Revolution of 1968! By Clemmie Harris

During the first two weeks of November peaceful protests led by Black students at Syracuse University drove national headlines after a series of racist and anti-Semitic attacks appeared on campus in the form of graffiti targeting Black, Native American, and Asian students as well as the appearance of a swastika drawn in snow at an apartment complex close to campus. Other forms of hateful written speech appeared that targeted Jewish students, including an anonymous email to a Jewish faculty member.

Adding to the spree of racist and anti-Semitic attacks, a “white supremacist manifesto” was posted online, which seem to be the same manifesto written by the person suspected in the March massacre at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand. Additionally, during the evening of November 16th fourteen people associated with the largely white Alpha Chi Rho fraternity, four of whom attend SU, shouted a racial epithet to a Black student.

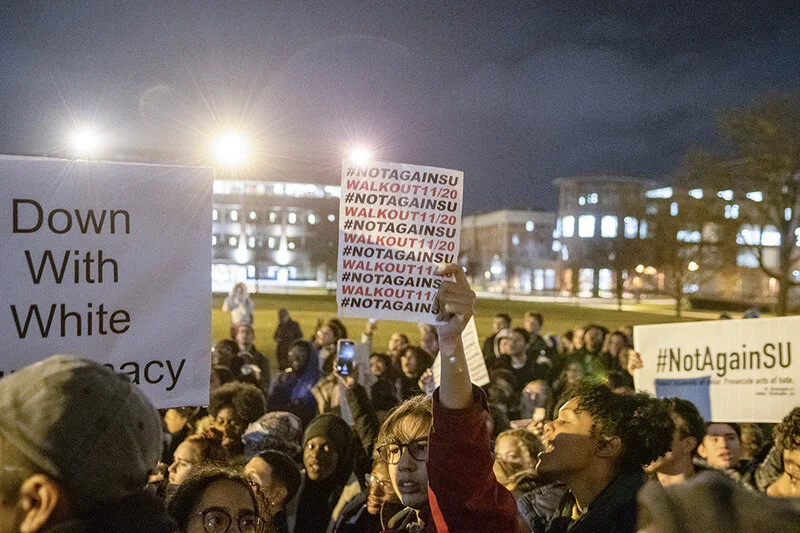

A total of sixteen separate racist and bigoted incidents across the university led nearly three hundred students to occupy SU’s buildings, including the Barnes Center at the Arch.

Student sit-in at Syracuse University (Jessica Tran)

Early perceptions of the university’s handling, or mishandling, of racist and bigoted speech also drove tensions. Angered by what they perceived to be a less than a fulsome initial response by university leaders to the spike in hate speech on campus, which included suspicions around the sharing of the white supremacist manifesto, as well as the chancellor’s hesitation to support all nineteen demands made by students, members of the student movement “#Not Again SU” promptly delivered a statement on social media demanding the resignation of the university chancellor.

The disputed demands included: the expulsion of anyone associated with hate crimes, mandatory requirement of diversity training for all new faculty and staff, the allocation of one million dollars toward the development of an anti-racism curriculum, and granting future residents the ability to select their roommates with mutual racial or ethnic identity. The chancellor disputed demands, according to the chancellor, required compliance from law enforcement or approval from the university’s Board of Trustees. “Syverud’s refusal to meet all 19 of the group’s demands and a failure to reach out to student organizers,” they stated, “justified a call for his resignation.”

Photo by TJ Shaw (Daily Orange)

For certain the #Not Again SU student movement was not only a direct response to recent racist and bigoted speech that targeted Black, Native American, Asian, and Jewish students, the hashtag selected by Black student leaders also points to the reoccurring nature of hateful attacks against Black students, students of color, and Jewish students on predominantly white university and college campuses, particularly those located in the North. Additionally, the hashtag and disputed student demands points to key flaws within the administrations of predominantly white institutions when it comes protecting historically vulnerable populations on campus.

There is zero doubt that the latest attacks on SU’s campus can be tied to the growing nature of racial, cultural, and religious intolerance triggered by the election of Donald J. Trump. Organizations such as the F.B.I., the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the Anti-Defamation League have all reported a rapid increase in racist, anti-Semitic, and Islamophobic attacks since the presidential election.

Photo from CUNY

However, there is another critical point of consideration. Recent protests by Black students at SU result from a historical process deeply rooted in the unresolved issues, or failures, of integration and American liberalism during the Civil Rights and Black Power Eras. As historian Martha Biondi has careful documented in her book, The Black Revolution On Campus, Black student revolutionaries attending predominantly white institutions protested over a wide range of issues that included racist and bigoted attacks from members of white fraternities, the right to shape their own education, which they did by demanding courses on Africa and the African Diaspora, they called for increased hiring of Black faculty and Black administrators, and they demanded the right to be housed with other Black students.

More than a half century later, student demands disputed by the SU chancellor are not fundamentally different from those demanded by Black student revolutionaries during the late 1960s. Additionally, the very fact that Black student leaders had to demand that the chancellor allocate one million dollars toward the development of an anti-racism curriculum exposes how neo-liberalism informs the administrative leadership within predominantly white institutions such as SU, which continues to experience tremendous growth in its pre-professional majors.

Clemmie Harris is Assistant Professor of History, African Studies, Urban Studies, and Public Affairs at Utica College