Maine Congressional Election an Important Test of Ranked-Choice Voting By Steven Mulroy

In Maine’s 2nd Congressional District, an innovative vote-counting system has had its trial run in a federal election.

No candidate received a majority of the overall vote in the 2018 midterms. Rather, the vote was split between four candidates – a Democrat, a Republican and two left-leaning independent candidates who garnered 8 percent of the votes between them. As a result, Maine used the ranked-choice voting counting process to determine a majority winner.

As a University of Memphis law professor, I’ve studied and published on ranked-choice voting for years, and have a book on it coming out next month. Naturally, I find the inaugural use of ranked-choice voting in a federal election fascinating. I also believe it’s a significant step forward for election reform.

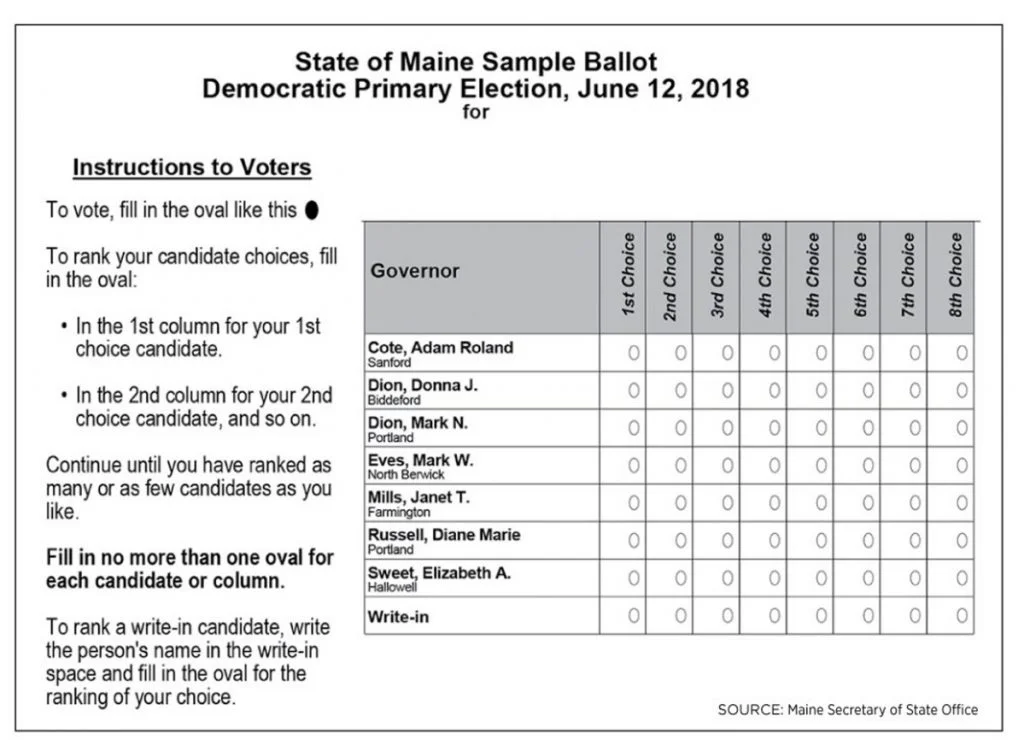

Under ranked-choice voting (more precisely, the variety of ranked-choice voting also known as “instant runoffs”) voters can rank their candidates in order of preference – first, second, third and so on. If no candidate gets a majority of first-place votes, the system eliminates the candidate with the fewest first-place votes. In Maine, that meant eliminating independent candidate Will Hoar, who got only 2.4 percent of the vote.

The system then redistributes the votes for that eliminated candidate among the remaining candidates based on the second choices indicated by voters. If a candidate now has a majority of votes, that candidate wins. If there’s still no majority winner, the system again eliminates the weakest candidate and transfers the votes as before, with the process continuing until there is a majority winner.

Ranked-choice voting is used in more than 10 U.S. cities. Six states use it for overseas ballots. Australia has used it for over 100 years. The Oscars use it, as does the Heisman Trophy.

Maine voters adopted ranked-choice voting by referendum in 2016. Court challenges and state legislative action delayed implementation, but voters reaffirmed their support in a second referendum in 2018.

Proponents cite a number of advantages of this system. It allows for a majority winner without the trouble, expense and historically low turnout of a runoff. By reducing campaign costs for the runoff, it levels the playing field for lesser-funded candidates, making elections more competitive. It also encourages civil campaigns. Candidates want to be the first choice of their own base, but the second choice of their opponents’ bases. Thus, they’re less willing to risk alienating those voters with attack ads.

Critics say ranked-choice voting is too confusing for voters, or too hard to administer. However, it has been successfully implemented in over 200 local elections in over a dozen U.S. cities over the past 20 years, without mass voter confusion.

Ranked-choice voting also solves the “vote-splitting” problem common to plurality, or “first past the post” systems, where a candidate can win with less than 50 percent as long as he gets more votes than other candidates. If too many candidates who reflect the majority’s view run, they will split that vote. That allows a candidate with 40 percent of the vote to win – even though 60 percent of the voters would say, “anybody but him.” Maine elected controversial Gov. Paul LePage with only 37 percent of the vote. During that election, liberal voters were split between a Democrat and a left-leaning third-party candidate.

Paul LePage (photo by Politico)

A similar dynamic occurred in Maine during the midterms. Two left-leaning independent candidates, Tiffany Bond and Will Hoar, got 5.8 percent and 2.4 percent of the vote respectfully, enough to deny both the Democratic and Republican candidate a majority.

Democratic nominee Golden ultimately won under ranked-choice voting. Many liberals who voted for the independent candidates ranked him second. As a result, this was the first time a Maine incumbent lost in over 100 years - demonstrating the rank-choice voting proponents’ claim that the system makes elections more competitive.

Fearing precisely that dynamic, Republican Poliquin who lost under rank choice voting filed a lawsuit challenging the process. A judge rejected his request for a temporary injunction blocking the ranked-choice counting process, but the underlying legal challenge continues.

The lawsuit alleges that anything other than a plurality election for the U.S. House violates the Constitution and federal civil rights statutes. But nothing in the text of the Constitution requires a plurality-only election for the U.S. House. The cases cited in the complaint merely say states are allowed to permit plurality elections, not that they must require them. Indeed, the Elections Clause of the Constitution provides that each state can “prescribe” the “Manner of holding Elections for … Representatives.” That’s how other states can and do require congressional candidates to win with a majority, using separate runoff elections where necessary

Moreover, this lawsuit is probably filed too late. The proper time to raise these issues would have been before the election.

For these reasons, I think the legal challenge will fail, and we will see, for the first time in U.S. history, a congressional race decided using this innovative new system.

Steven Mulroy is Law Professor in Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, Election Law, University of Memphis

This article originated at The Conversation