Europe in the Age of Secession By Nathan Richmond

Development of the European Union

In the early 1990s the USSR (and Yugoslavia) unraveled as George F. Kennan predicted at the onset of the Cold War soon after WWII. Paradoxically, this movement to create new, independent states in Eastern European coincided with the opposite trend occurring in the rest of Europe with the expansion of, and the deepening of, ties among the member states of the European Union.

In the early 1990s the Maastricht Treaty paved the way for the transformation of the European Community (EC) into the European Union by establishing three "pillars" of cooperation: a single currency, a common foreign and security policy, and a common justice policy. In the mid 1990s, Austria, Finland, and Sweden, no longer fearing Soviet objections, joined the EU. And in the late 1990s and early 2000s, subsequent treaties (Amsterdam and Nice) resulted in the further delegation of powers from national governments to the EU and paved the way for a rapid expansion from 15 members to 25, including some states which had been part of the USSR and others which had been part of the Soviet bloc, in 2004.

Image by BBC

The expansion of EU membership continued with the admission of Bulgaria and Romania in 2007, but the onset of the European financial crisis led some analysts to question the viability of the EU's common currency, the Euro, and others to question the continued existence of the EU itself.

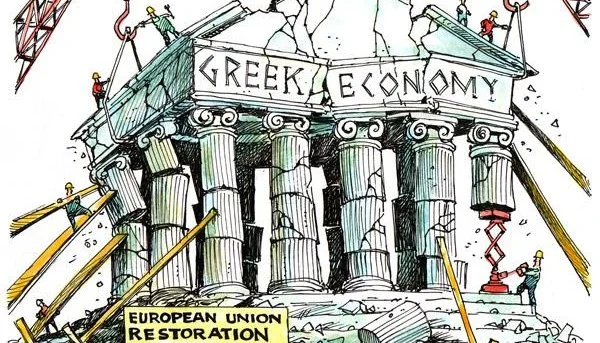

The Greek Financial Crisis and the Threats of Expulsion

In 2009, due in part to the US Great Recession which began in 2007-08, the Greek Debt Crisis exploded. As successive Greek governments balked, then accepted the stringent austerity terms imposed by other governments and international financial institutions, there was frequent speculation that Greece would be expelled from the EU. Then when other EU states, notably Portugal, Spain, and Italy were struck by the financial contagion, there was widespread speculation that the EU could not, and would not, survive. In fact, it did survive, and added a new member, Croatia, in 2013.

Dave Granlund

Brexit, Frexit, Grexit, and Other Threats to the EU

The Brexit vote of June 2016 laid the foundation for Britain's withdrawal from the EU. Following the success of Britain's Brexit campaign, politicians in the Netherlands, France, Greece, and elsewhere each promised to hold a national referendum on their country's continued EU membership if elected. None of those populist-nationalist parties succeeded, although the newly elected conservative-right wing coalition government in Austria may hold just such a referendum in the future.

The rise of authoritarian governments in Hungary and Poland are testing the limits of policies acceptable to a democratic EU. Hungary's Prime Minister, Victor Orbán, has been accused of "suffocating civil society." Openly defiant of Brussels' policies and norms, especially regarding immigration and refugee resettlement, Orbán has also placed party loyalists in formerly neutral positions such as the prosecutor's office, the central bank, and the central election commission. He has shut down opposition media outlets and openly praises the Russian, the Chinese, and the Turkish governments while criticizing other EU ones.

Photo by Patrick Seeger

Poland's government is also at odds with Brussels. Warsaw and Brussels are clashing not only on the issues of immigration and refugee resettlement, but also on recent reforms giving the Polish government more control over that country's judicial system, and their mass media. And the Polish government is also engaged in open conflict with and defiant of the EU on an important environmental issue as well. There is widespread speculation that Poland's government may be planning on leaving the EU, perhaps in tandem with Hungary.

The Threat From Secessionist Movements

The latest threat to the viability of the EU comes not from the voluntary withdrawal or threatened expulsion of member states, but from the multitude of independence movements which threaten the continued existence of several of the member states, both large and small.

In Catalonia, which already enjoys a high degree of autonomy in Spain, the crisis is reaching a dangerous level. Catalans who voted in the October 1 independence referendum voted overwhelmingly (over 90 percent) for independence, but only 43 percent of eligible voters voted. The Spanish government, with the backing of the judiciary, declared the vote illegal, and used massive violence to suppress the vote.

Photo by Josep Lago/AFP

Since then, the Catalan regional government has declared the region's independence, but "suspended its implementation pending negotiations with the Spanish government." In response, the Spanish government gave the Catalan regional government a brief window, originally until October 17, now until October 19, "to clarify if they have declared independence or not." If so, the Spanish government is prepared to revoke Catalan autonomy and reimpose direct rule from Madrid. On October 16, the Spanish government escalated the crisis by arresting two who helped organize the referendum and subsequent mass demonstrations and is considering charging them with sedition.

While the Catalan crisis is unresolved as of now, the stakes are clearly very high. If Catalonia is successful, it will encourage other separatist movements in Spain and in other countries. In Spain alone there are separatist movements in the Basque Country, Castile, Andalusia, Galicia, and other regions. France, which has its own Catalan and Basque regions, and separatist movements in Brittany, Corsica, Savoy, Provence and elsewhere, has criticized the Spanish Catalans for their efforts.

There are separatist movements in Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in the EU, including Germany. While at the moment it appears that none of these independence movements will succeed any time soon, some observers are already pointing to these trends as "the beginning of the end of the European nation-states."

For some, the breakup of large European states into independent regions should have no effect on the EU. Those who subscribe to this viewpoint take Scotland as an example: UK out of the EU; Scotland in. While such a scenario may or may not come to pass (some British are opposed to another Scottish independence referendum: "one and done"), there is a real fear among EU leaders that the Catalan independence movement will energize similar movements across Europe.

The Catalans have asked the EU to mediate their dispute with Madrid and have been firmly rebuffed. EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker does not see the "Scottish Solution" as described above as a viable alternative. "It is already difficult managing with 28, soon to be 27 members," according to Juncker. "Ninety-eight members (if all the independence movements succeeded) would be impossible."

The EU can survive the withdrawal of the UK, and even the additional departure of Poland and/or Hungary. But it may not survive if separatist movements prevail in Spain, Italy, France, and elsewhere.

Nathan Richmond is Professor of Government at Utica College